Vaccine Hesitancy: A Case for Compassion

I want to open this by sharing both that I emphatically believe in the safety and efficacy of vaccines and that I used a delayed vaccine schedule for Rónán when he was a newborn. I had never taken any courses in epidemiology or vaccine development, so I based my choices as a mother on the best information that was presented to me.

That said, if I have another child, I will vaccinate them according to the CDC schedule. I have no reason to believe that Rónán or his future sibling will experience anything more than a sore leg and a low-grade fever in exchange for immunity to the 17 diseases it covers. We’ve had other vaccines for travel (Japanese Encephalitis and rabies) and Hypothetical Future Baby will have those as well.

The purpose of writing this isn’t to shame parents who are vaccine hesitant or vaccine resistant or even to convince you with data. The purpose isn't to make anyone feel like they don't love their children enough or somehow aren't smart enough to be parents. (Or, honestly, to make you think that I think those things.) The point of writing this is to speak to the parents who are frustrated and frightened by the declining immunisation rates in places like Vashon Island in Washington State or are worried when they see a notice come home that there’s been an outbreak of a vaccine-preventable disease in their child’s school. It’s scary for parents whose children are potentially exposed and school exclusions, while effective, can cause frustration in affected communities.

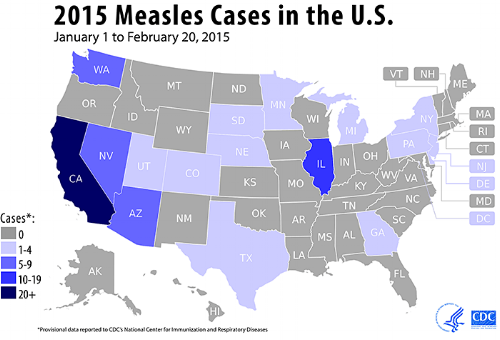

US cases of measles (1 January-20 February 2015)

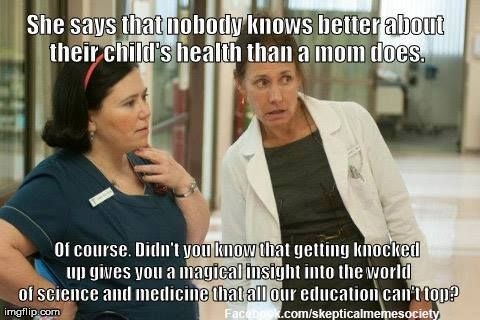

Washington State just had a severe mumps outbreak and I saw plenty of parents (and non-parents) lamenting on social media that “those people” should “just vaccinate their [expletive] kids.” I also saw (and heard) people saying that parents who don’t vaccinate (or delay vaccination) are “stupid” or “don’t love their kids” enough to protect them.* I've heard people wish vaccine preventable diseases on unvaccinated children. I hear the fear behind those statements, but name calling and saying that parents don’t love their children because they feel anxious about vaccination is unkind, unhelpful, and not accurate. Not all parents show love in healthy ways, but parents, in general, act in what they reasonably believe to be the best interests of their children based on the information available to them.

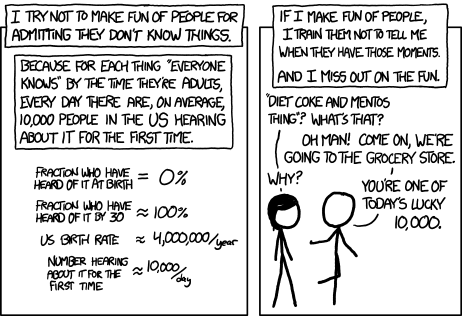

There’s inherent classism in the assertion that people who have not taken epidemiology or biostatistics are “stupid.” It’s a common joke to mock the “antivax” parent who declares that they’ve “done [their] research,” but how fair is it really to mock them as being unintelligent? While googling isn’t the same as working at a lab bench, it’s really expensive to study epidemiology. It costs $3,460 to take just the first course in the epidemiology series at the University of Washington. To take the whole basic epidemiological methods series (8 credits) is $5,992. That’s leaving off the biostatistics, microbiology, and immunology courses that are also fairly standard among public health students. (Epidemiology and biostatistics are required, the other are just common.) That’s a lot of time and money for information that isn’t taught below the undergraduate and graduate levels. Honestly, it’s only seldomly even available for undergraduate students. The majority of people never go to graduate school and even fewer for a health discipline. Are they all stupid?

Not helpful, just classist and misogynistic

Even if we’re talking about someone who does have access to the kind of training that they could read and understand the scientific literature on vaccination, most of it is locked behind the academic paywall. With most academic journals, you can pay around $400 each year for each journal (making you more likely to have less diversified information) or you can pay around $39.99 for each individual article. To give you a sense of how quickly that can add up, when I’m writing a paper for a course, I usually pick over around 25 papers—that’s a quarter shy of $1,000. “Doing your research” looks a lot more expensive, doesn’t it? I’m very fortunate that I have access to journals through work and through school, but that’s a privilege that I’ve paid for by participating in (and paying for) academia. The average person who just wants to know what’s in the flu vaccine their baby is receiving doesn’t have that luxury.

Now that we’ve established that it’s quite challenging to access information through peer-reviewed journals and that most people (through no fault of their own) have never been presented with the epidemiological training to understand it, let’s move on to the classic way people have accessed medical information: at their doctor’s office. In America (and many other countries) doctors are seen as being founts of knowledge and trusted sources for answering your tricky questions about which drug or procedure you need to fix what ails you.

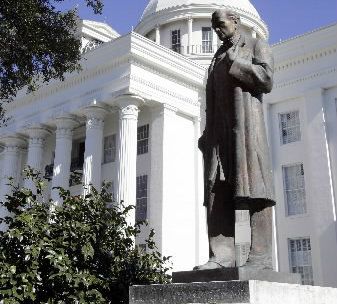

Statue of Dr. Sims Image (via Alabama Life)

For some communities, there is a long (and justified) history of distrusting the Medical Establishment. In the early 20th century, the US Public Health Service conducted a study on 600 African American men without their consent called the Tuskegee Syphilis Experiment. Around 2/3 of the men had syphilis at the beginning of the study, but not all of them did. The researchers did not tell the participants that they would never receive treatment for syphilis (though penicillin was standard by 1945 and the study ended in 1972). The study was criticised as early as 1936 for denying the men treatment, but the CDC eventually convinced the local medical associations to support it. At no point was what was happening ethically acceptable, but the medical establishment decided that watching the full progression of syphilis infection was worth the lives of 600 black men in Alabama. Nevertheless, the Alabama State Capitol has a statue honoring Dr. J Marion Sims, who headed the study.

In Washington State, our Russian-speaking population has a high proportion of vaccine hesitancy—the highest in the state. A 2015 assessment of vaccine hesitancy among Russian-speaking residents of Washington State found that member of that community struggle to find a Russian-speaking provider to answer their questions and that they distrust the schedule because it's so different than the ones in their home countries. When asked where they would prefer to receive information about vaccination, 55% shared that they would prefer community meetings over just conversations with a provider, possibly a result of existing distrust of the Soviet political and medical establishments.

The majority of children are vaccinated, but we’ve amped up the tension around “those parents” who leave everyone else’s children vulnerable and that’s changed the narrative in exam rooms. When a parent is hesitant about vaccination, some physicians may ask them to leave the practice completely and nothing makes me dig in my heels faster than someone telling me that I have to/cannot do something—especially if that something involves my parenting. Now these children aren’t vaccinated and they’re out of medical care. This brings us to two questions which we as a society need to examine:

- If these parents can no longer ask a trained medical provider for health information, where will they turn for future questions? An evidence-based (but maybe less trusted) resource like the CDC or somewhere that looks both independent and trustworthy (though may be neither) like the National Vaccine Information Center?

- If they should come down with an illness (as they are more likely to do), where will they access their care? From an urgent care clinic or emergency room where the providers don’t know them or their medical history? How likely are they to take the time to find a new family medicine provider when they’ve just been treated poorly by one? It's hard to find a new provider, particularly when you're on Medicaid or uninsured. Do we truly want those children to fall out of care?

These are hard questions, but it’s important that we sit with them and think about the best way to present information. There’s so much fighting on the internet and this is a heated topic on the best days. I’m not saying that we shouldn’t have conversations or the medical providers shouldn’t advocate for children to be appropriately immunised, but we need to do it in a way that maintains a respectful, open dialogue and invites people to ask questions and have their concerns heard. As I said above, we all love our children and want what is best for them. We all want our communities to be safe and healthy, but there are ways that make it harder to have productive conversations and banning children from medical practices and screaming at their parents on the internet aren’t among those best ways.

What's Next?

If you'd like training on how to deliver public health communications, I've created a list of some resources on risk communication below.

- The Center for Risk Communication

- Crisis and Emergency Risk Communication (CDC)

- Emergency Risk Communication Training (WHO)

- Introduction to Risk Communication (Johns Hopkins)

- Crisis and Risk Communication (FEMA)

* I'll note here that the mumps outbreak in Washington was concentrated in a highly vaccinated population, making such criticisms both unkind and not relevant to the epidemiology of that specific outbreak.