Health: More than Healthcare

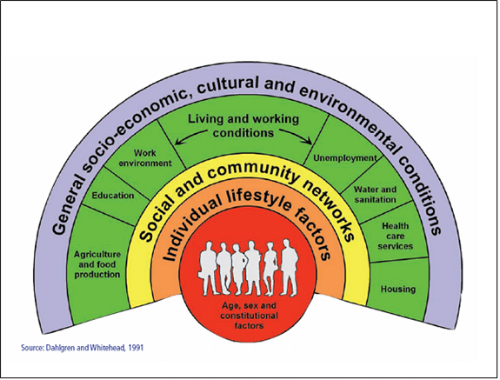

When we think of our health, our first thought is usually of going to see a physician (or other medical provider) and having tests like an MRI done, but access to medical care only makes up a small proportion of our overall health. Our health is shaped much more by the social determinants around us–the air we breathe; the water we drink; the amount of education we have; the safety and accessibility of our housing, nutrition, and public transportation. Together those factors build a framework that we call “The Social Determinants of Health.”

Because it doesn't always feel intuitive to frame our health this way, the Association of Schools and Programs of Public Health (ASPPH) runs a campaign called #thisispublichealth to raise awareness of all the ways that public health is working to keep you healthy. The videos for the campaign typically show public health students plopping stickers on things in their community that they identify as being public health. Some of the choices feel unsurprising (an ambulance and a health clinic) while others feel much less expected (a grocery store and a fire hydrant). The idea is to get people thinking about public health as really being "health in all policies" because literally everything around us is connected to our health.

Social Determinants of Health (Policies and Strategies to Promote Equity in Health)

In Canada, there is an exercise to help illustrate the way our Social Determinants work together to make us healthy (or unhealthy):

The Social Determinants are often neglected when we talk about our health, but they’re far from a new way of thinking. In 1915, the first director of the United States Children’s Bureau, Julia Lathrop, noted in the New York Times that infants from poor families died at significantly higher rates than those from wealthier ones. [1,2] The trend continues today both between nations and within smaller communities, extending far beyond health outcomes in the first year. The infant mortality rate in Mozambique is 120 per 1,000 live births, but in Sweden it is 2 per 1,000 live births; [3] the lifetime risk of maternal death is 1 in 17,400 for women in Sweden, but only 1 in 8 for Afghani women. [3] Neither the babies in Mozambique nor the women in Afghanistan are inherently more frail than their counterparts in wealthy settings. What we’re seeing is the difference in the social determinants of life that they are living and the amount of resources to which they have access. Mothers and babies in Sweden have access to better nutrition, transportation, housing, and medical services than their counterparts in Mozambique and Afghanistan, and that makes them healthier.

These disparities–unequal outcomes in health–appear early in life and continue throughout it if there are no interventions to improve the social conditions in which a person lives. “As early as nine months, measures of cognitive development, social-emotional development, and general health are worse for poor children,” [1,4] emphasizing the importance of early interventions to improve long-term health outcomes. The graph below [1] illustrates the lifetime risk of death in relation to household income in the United States, showing a “dramatically higher” risk among those living below the poverty line than those above it. Like the differentials between maternal and infant mortality rates, it is incorrect to assume that America’s poor are inherently less healthy than its middle and upper classes. The disparity, again, is a reflection of societal conditions.

Even a seemingly innocuous issue like transportation has deep significance on access to other social and health services, as well as the overall quality of life for the entire household. As in the case of Johnny’s mother Susan and her husband, long commutes on public transportation create far longer workdays and significant stress between the struggles to pay rising fares, to negotiate perpetual transit cuts, and to make difficult transfers (often multiple times). Lack of adequate transportation is, for 75% of Colorado communities surveyed by the Colorado Commission for the Medically Underserved, a major health issue, noting that it was a significant barrier to care. [5] Difficulties in making it to appointments on time and in navigating to unfamiliar, potentially less accessible specialists’ offices for some patients deter them from scheduling future visits. [5] For chronic conditions this is particularly troublesome as they often require longterm followup care for effective management.

The Take Away

Clearly the infection in Jason’s leg is why his parents brought him into the hospital, but the social factors that created a situation in which he would get hurt are part of the problem too. It’s easy enough to treat the infection; tackling those other issues is much harder. In public health, we call these the “upstream problems” and, like a salmon trying to get home, it can be challenging to reach them. How do you “fix” an environment like Jason’s? Building an open space for children to play (an empty lot cleared of unsafe debris may be an option), but what about the lack of supervision for the children? Or the unsafe housing? Or employment and education? How do we fix those problems?

I don’t have easy solutions for correcting those social challenges, but solutions do exist. Raising educational standard in K-12 and making college education more accessible would help. As would policies supporting safe and affordable housing.

We need to be thinking about the realities of poverty and how we can help to raise our communities out of it. I don’t mean that individual work shouldn’t matter, but more that we are all healthier when our communities thrive. When my son arrives at school fed and healthy, he’s less likely to spread infectious diseases to other children (and their families) and more likely to be prepared to learn the skills he’ll need as an adult to support the his own family and the economy. When children grow up in healthy families they sustain health communities from which we all benefit.

Right now the United States’ health is ranked at the bottom among wealthy nations, [6] but not because we don’t have enough MRIs and chemotherapy available. We’re at the bottom because we neglect the social determinants of our health. It may feel counterintuitive to reframe bus lines and school lunches as public health, but, we have to start thinking about the Social Determinants if we want to be the world’s healthiest nation again.

- Robert Wood Johnson Foundation. The Poor Pay More–Poverty’s High Cost to Health. http://www.rwjf.org/content/dam/farm/reports/reports/2009/rwjf47463 Published September 2009. Accessed 24 September 2014.

- New York Times, February 7, 1915. As cited in above RWJF report.

- World Health Organization. Committee on the Social Determinants of Health. http://www.who.int/social_determinants/thecommission/finalreport/key_concepts/en/ Published 2008. Accessed 23 September 2014.

- Nepomnyaschy L. (2009) Socioeconomic gradients in infant health across race and ethnicity. Maternal and Child Health Journal; 2009 Nov;13(6):720-31. doi: 10.1007/s10995-009-0490-1/

- Colorado Commission for the Medically Underserved. Social Determinants of Health. Denver, CO. 2013

- Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development, Health at a Glance: 2015 OECD Indicators, November 2015 http://www.oecd.org/health/health-systems/health-at-a-glance-19991312.htm

By: Amanda