We've Been Here Before: Learning from Historical Responses to Epidemics

Scoping the problem

As we close the month of June, the United States also closes out the 5th month of COVID response in this country—and we’re not even close to done with this pandemic. In these 5 months, we’ve learned a lot about the SARS-CoV-2 virus which causes COVID-19 and about ourselves. During these months, epidemiologists (like me) have watched in horror as our efforts to control the spread of the disease have been thwarted—sometimes, it seems, intentionally—by people in power. It’s been shocking and heartbreaking to watch case counts here in the United States plateau only to spike again. It’s been particularly agonising watching Nations like the Yakama and Navajo be so consistently denied the resources they need to protect their communities.

The graph below shows the daily number of new cases reported to the World Health Organisation by the WHO region where the case lives, as reported in COVID-19 Situation Report 160. You can see that nearly all cases through the end of February were reported in the Western Pacific Region (which included China), followed by a large wave of cases in the Europe region which plateaued in early to mid-May. You’ll also notice that cases in the Americas increase sharply from the end of March and continue both to escalate as time continues and to dominate the bulk of cases globally.

This trend would be worrying even if the burden was shared equally across countries in the region, but it’s horrifying that the vast majority of these cases are occurring in the United States.

I recognise that graph may be a bit hard to contextualise with regard to US cases of COVID-19, so I pulled down some of the data from the WHO COVID-19 Situation Report for today. As of 28 June 2020, there have been 4,933,972 cases of COVID reported in the Americas region. Of those, 2,452,048 have been reported in the United States. This means we have 49.70% of the cases and despite making up just 33.18% of the population for the region. Even without taking into account that the United States as a large, wealthy country should have some of the lowest communicable disease numbers, this discrepancy is shocking.*

Something is clearly wrong here and the course needs to be corrected. It’s not impossible to break the chain of transmission, but it takes hard work and plenty of bravery on the part of elected officials. Thankfully, history is littered with success stories when humans have controlled the spread of diseases. For some of these lessons, we don’t even have to look back farther than a half century.

Testing and Case Counts

It was suggested recently that the United States has high case counts because we’re doing so much testing and, while it’s true that you identify cases when you test people for a disease, more testing = more cases is a gross over simplification of the equation.

The United States is consistently failing to meet our testing goals. We are testing more than we were, but it’s still not even close to enough. We cannot break the chain of transmission from one person to the next if we don’t know where transmission is occurring…and we don’t know where it’s occurring if we don’t actually look for it.

While identifying cases of COVID does increase case counts, at least initially, it doesn’t increase transmission and so case counts will go down if containment measures (like isolation and quarantine) are used when a case is identified.

Watching case counts rise can be devastating, but stopping testing isn’t the answer. Even slowing testing isn’t the answer. When we test for COVID, we’re identifying what’s already slipping through our communities, snatching loved ones and strangers from the lives they deserve to be living. People don’t stop being sick because we’re not counting them. We tried limiting testing in January and February and look at where they got us.

The only responsible way to control this pandemic (if we’re not just going to close everything indefinitely) is to identify every single case we can, to trace all their contacts, and to contain the spread with isolation and quarantine. The undercounting of cases by halting their identification and reporting is not a responsible strategy to reduce the number of cases reported each day. Pretending the disease isn’t there just prolongs the pain of this pandemic by keeping transmission in the shadows where we can’t control it. The devastation of this pandemic is there even if you’re not looking for it. When you close your eyes to a pandemic and just let it circulate, you’ll still see the evidence of the infections in the excess deaths, in the higher percentages of clinical encounters for an unexpected symptom profile, in the lack of ICU beds. You’ll see the evidence in the continued suffering of communities.

More testing doesn’t mean there are more cases, it means there are more identified cases. Identifying cases means we can tell those people they’re sick and help them not transmit the disease to others, which then lowers case counts. That’s how we break the chain of transmission.

Lessons from the Eradication of Smallpox

Dr. Bill Foege is one of my heroes. He’s a physician and epidemiologist (as well as a fellow UW alum) who headed the effort to eradicate smallpox in the 1960s and 1970s. He describes this incredible fight in his 2011 book House on Fire: The Fight to Eradicate Smallpox, which I recommend to everyone who wants to fill their heart with inspiration. The details of the eradication effort described below are taken from his description in House on Fire.

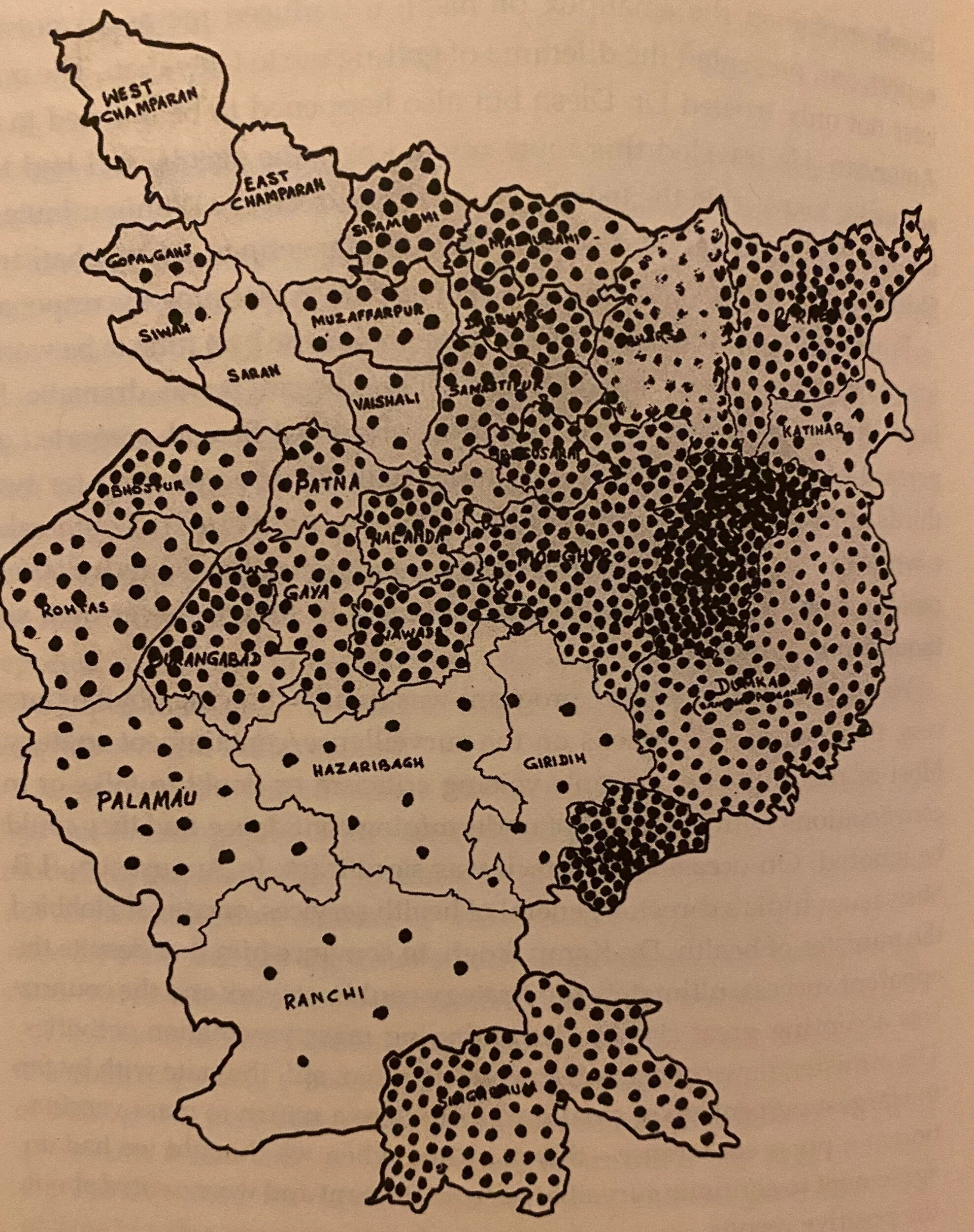

When Dr. Foege was deployed to India, the task of eliminating smallpox seemed insurmountable. To give you a sense of the scope, smallpox killed around 30% of people infected and there were hundreds of thousands of cases every year. India was one of the last countries to still have wild smallpox circulating and had several states which were considered smallpox endemic, meaning that the disease was always circulating through the community. Bihar, in particular, had very, very high transmission.

Mass vaccination had previously been the primary (read: only) strategy being used to control the disease and it really, really wasn’t working. So, one of Dr. Foege’s first tasks was to do broad, deep surveys to identify all the cases of smallpox they could to get a sense of how widespread the problem was. Working with teams of incredible doctors, nurses, and “special epidemiologists,” he was able to do what had previously seemed impossible. They rode ferries, slept on trains, hired guards to vaccinate anyone entering the house of a person with smallpox, and paid rewards to community members who identified undiscovered cases. His field staff went out to villages across Bihar and found more cases of smallpox than had ever been found before.

New outbreaks detected from 28 January - 2 February 1974, from House on Fire (Foege, 2011)

New outbreaks detected from 27 January - 1 February 1975, from House on Fire (Foege, 2011)

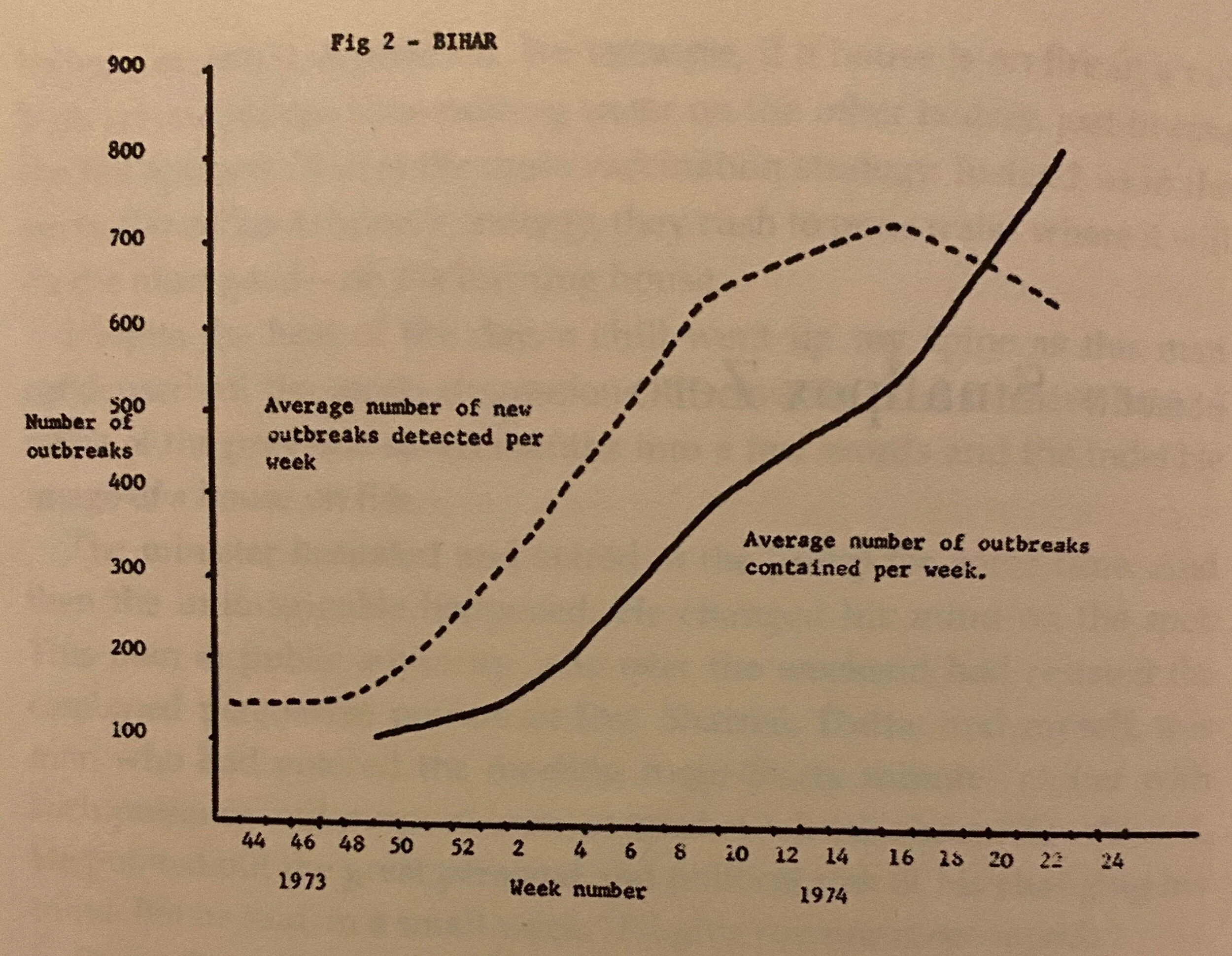

The smallpox teams shifted from mass vaccination to a policy that prioritised identification and containment—and the case counts continued to climb. After a year or so of this, ministers who had previously been supportive of the campaign to eliminate smallpox in India started to worry that the campaign was causing more problems than it was solving. How could they be eliminating smallpox when the cases always went up? On several occasions, the campaign was almost ended before it could demonstrate that it was working.

However, each time this happened, Dr. Foege and his colleagues would share their data on not just the number of outbreaks (connected cases) they had identified, but also the number that they had contained. For much of the campaign, the number of contained outbreaks struggled to overtake the number of identified outbreaks, but then in 1974, a year before elimination, it finally happened. The smallpox team was winning the fight against one of the deadliest diseases on the planet be identifying and containing the disease. Dr. Foege predicted that the chain of transmission in India would be broken in May the following year and he was right.

Average number of outbreaks detected per week and average number of outbreaks contained per week in Bihar by MMWR week number (1973-1974), from House on Fire (Foege, 2011)

Tying it Together

When I read House on Fire, I was struck not just by how strong and resilient his team was (or how much I adore Dr. Foege), but also the parallel with our own struggle to contain COVID. There were times when ministers were worried that the smallpox eradication effort was a danger to their career or making their country “look bad,” but they always ultimately chose to prioritise the well-being of future generations who had a fighting chance of living lives forever free from smallpox.

Their efforts to identify all the cases, all the outbreaks did make case counts look higher—but only because they were finding what was already there. Their efforts to identify, trace, and isolate ultimately lowered transmission until the disease no longer existed. If the Indian Government and the WHO had told Dr. Foege and his team that their strategy to eliminate smallpox was making them look bad because case counts were so high, we’d still be losing millions of people a year to that disease instead of studying it in history books. We’d still be vaccinating every child against smallpox in the hope that we could protect them from that death.

it took tremendous bravery for those ministers to continue to support a program that wasn’t guaranteed to work and which was finding more cases of smallpox with every search. It took deep commitment to public welfare then and the response to COVID requires the same of our leaders now.

Ramping up COVID testing does make case counts look higher—but only because we’re finding what’s already moving through our communities. We’re finding what’s there and that strategy can eventually get us to a place where transmission is controlled and it’s safe to live again. We’ll never fully eliminate COVID since it can lurk in other mammals (bats, cats, and maybe pangolins), but we can get to a place where we can see our families again and that’s a big mark in the W column.

World Health, Magazine of the World Health Organisation (May 1980)

*Also worryingly, approximately 25% of cases in the Americas Region are in Brazil. The remaining 25% of cases in the region are spread among all other counties. Brazil’s president could also do with some reviewing of his country’s historical wins against diseases like Yellow Fever.