When Poor Air Quality Strikes: Keeping Safe When It Snows Ash

The air over Seattle (and the rest of the Pacific Northwest) has been very poor lately. The concentration of PM2.5 (very small bits of particulate matter in the air) has been well above what health officials consider acceptable for human health. The situation is even worse up north in Alberta when the sky seems to be permanently yellow like a scene from some kind of post-apocalyptic dystopia video game my partner would play.

Air quality over Seattle, Washington from June to August 2018. Image via @SMS0918

There's been a lot of worry for what the air quality means for our health and why it's happening, as well as the completely understandable fear that this is our new normal. I'm going to talk a bit about what's in the air, who is at risk of poor health from it (spoiler: everyone), and some ways that you can try to keep yourself and your family healthy when these events happen.

As always, please don't substitute what I say here for your medical provider's advice or a local medical clinic. If you have a worry, please call their office or your local health department.

Why is the sun magenta in the morning?

Although we've now had several years of poor air quality events in the summer, last year was my first since I'd been abroad during the previous ones. The summer camp my son attends is just over the hill from us and I have an excellent view across a local lake most mornings, but, during poor air quality events, I can't even see the bottom of the hill, let alone the city across the lake from us. Despite the (now obvious) cause of the poor visibility, I was confused about why I was wheezing during brisk walks and why my eyes were constantly irritated. Looking back over the air quality data from the previous 3 years, the picture makes a lot more sense.

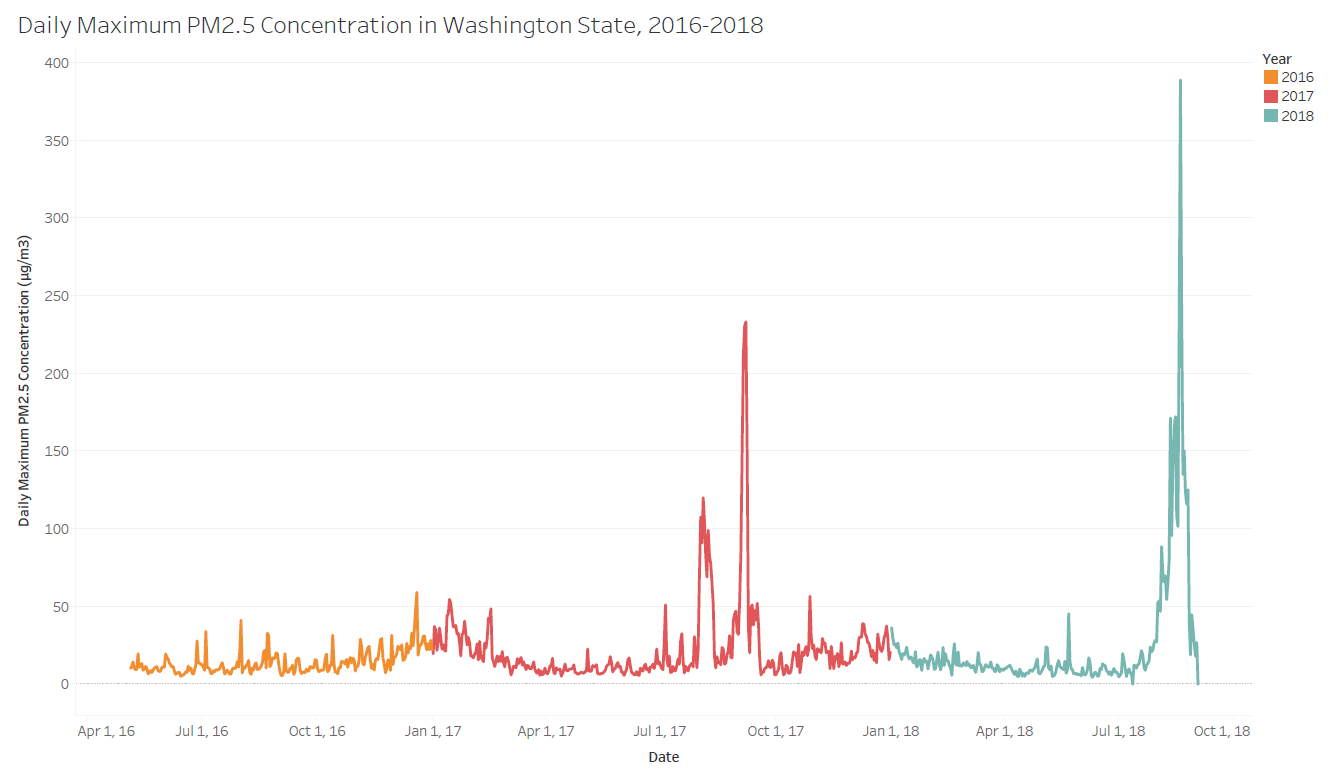

Daily maximum PM2.5 concentrations in Washington State, 2016-2018

The graph above shows the daily maximum PM2.5 concentration for Washington State between May 2016 and the beginning of September 2018 with the years in yellow, red, and blue. As you can see, the maximum daily PM2.5 spikes in the last two summers and our highest spike in 2018 (389 µg/m3) was more than 1.6 times as high as the previous summer (233.3 µg/m3).

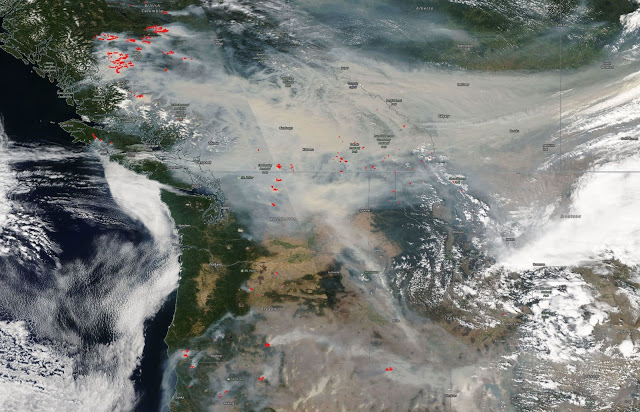

So what's caused all this mess? Massive wildfires (and lots of them) in Alberta, British Columbia, and California added their smoke to the fires in our own state and combined to make a truly awful landscape. The smoke has been building and billowing across western North America all summer and, while it's finally slowing, there is still plenty of smoke in the air.

So what's the fuss then?

Via the Ottawa Citizen

Why does it matter if the air is dirty? How does poor air quality influence human health? Poor air quality is responsible, either directly or indirectly, for an estimated 5.5 million people's deaths every year. That poor air quality isn't all down to wildfires (a lot of it is from industrial pollution and indoor cooking over open flames) but wildfire smoke absolutely has health risks. Respiratory and cardiovascular (heart) conditions can develop or be exacerbated (e.g., more asthma and heart attacks), eye pain and irritation are common, and having lower blood oxygen is bad for you all around. In some severe cases, like in areas where the smoke is thickest near the fires, it can be dangerous to breathe the air for even a few minutes and visibility may be so poor that driving is dangerous.

While all people suffer when the air quality is poor, some people are more vulnerable to its effects than others. Epidemiologists (apparently lacking creativity) call these groups "sensitive populations." Children (particularly those under 5 years of age), adults 65 years of age and older, pregnant people, and individuals with underlying medical (especially respiratory and cardiovascular) conditions are all considered "vulnerable" when poor air quality strikes. Public health organisations work hard to monitor air quality and issue alerts when the air is at levels considered dangerous for different groups. They also work to supply masks and support health care facilities which may see larger volumes of patients seeking treatment for care. No person is immune from the effects of poor air quality, although sensitive populations are at the highest risk for complications.

So what can we do?

Air quality recommendations via Puget Sound Clear Air

1. We can be mindful of air quality warnings where we live and follow recommendations for our "risk group."

Listen to your body and watch for signs of exhaustion. When possible, try to limit time outdoors when you're feeling poorly. If it's recommended and you can, try to wear a NIOSH-approved mask to protect yourself.

Groups like Puget Sound Clean Air give very specific recommendations by geographic region for activity levels for each risk group. The Canadian Government has a very helpful site with general information about air quality risks and local air quality data. There are almost certainly equivalent groups where you live; googling "air quality data" and the name of your region should provide you with helpful information.

2. We can communicate public health recommendations to our friends and neighbours.

Public Health tries really, really, really hard to communicate what's happening in emergencies like poor air quality events. Unfortunately, we don't always reach everyone. Sometimes we're not using the right communication platforms (radio, television, social media), sometimes we haven't covered all the local languages, and sometimes our messaging itself wasn't clear enough. You can be of tremendous help to your local community and its public health infrastructure by reaching out to your friends, family, and neighbours to make sure they know what the current recommendations are for your region.

3. We can help prevent forest fires.

I don't want to sound like Smokey the Bear, but quite a lot of forest fires are preventable. Last year, the Eagle Creek Fire which ravaged the Oregon-Washington border was started by reckless teenagers who threw lit fireworks into a forest ravine during a months-long burn ban. The fire burned 50,000 acres and lasted more than 3 months. Not every preventable fire was caused by such monumental irresponsibility, but other choices we casually make (like throwing a lit cigarette out of our car window) are also common sources of fires. Thinking carefully about how we interact with the spaces around us can make a big difference in the health of our communities.

2017 Eagle Creek Fire via Oregon Live