Why They Stay: The Challenges with Evacuating Communities in an Emergency

As I write this, Hurricane Florence is devastating the Carolinas on the east coast of the United States and, as with previous storms, there are questions flying about why people in the evacuation zone have chosen to remain in their homes and “shelter in place.” Although many people leave when local authorities declare their home inside an evacuation zone, there are always some people who remain despite the warnings. Why do they stay? Don’t they know they’re in danger? Don’t they care?

The short answer is that evacuating is complex and can be very, very expensive for the person leaving. Paying for gas (if you can get it before the stations are emptied), booking hotels, renting a car (if you don’t have one), and getting time off work are all major financial concerns for many, many Americans. Whether you shelter in place or evacuate, you may need to buy food, water, and supplies like batteries. If you have pets (as most Americans do), that’s another expense to accommodate since the hotels which take pets (not all do) generally charge a hefty fee for each night they stay.

It’s not possible for me to share all the personal and structural challenges to evacuating communities from disaster zones, but my hope is that this post provides some insight into why so many individuals remain in the path of natural disasters.

What does it really cost to leave?

How big a burden is the cost of evacuating? Let’s add up a sample tally for a storm which requires a family of 3 to evacuate their home for 5 days. For now, let’s assume that our Hypothetical Family owns their own car which can transport them a sufficient distance to escape the worst of the storm (not everyone does) and has no pets:

Hotel: $80 per night for 5 nights plus local taxes and fees (often around 13%) → $452

Gasoline: $3.50 for a 13 gallon tank → $45.50

Food and water supplies: $35 per day for 5 days for each person → $525

Total for very basics → $1,022.50

If our Hypothetical Family lived in an urban environment (as many people affected by Hurricane Sandy did), they might not have had ready access to a car to get away from the evacuation zone. If they are able to secure access to a rental car (competition may be fierce!), they can expect to pay several hundred more dollars. When I checked Enterprise rates for 5 days, I was quoted $688.35 for an economy car. If our Hypothetical Family’s child is under 10, they will also need to rent a child seat (around $10 per day). When we add this expense to the previous total, we’re now at $1,760.60 for the basics necessary to evacuate.

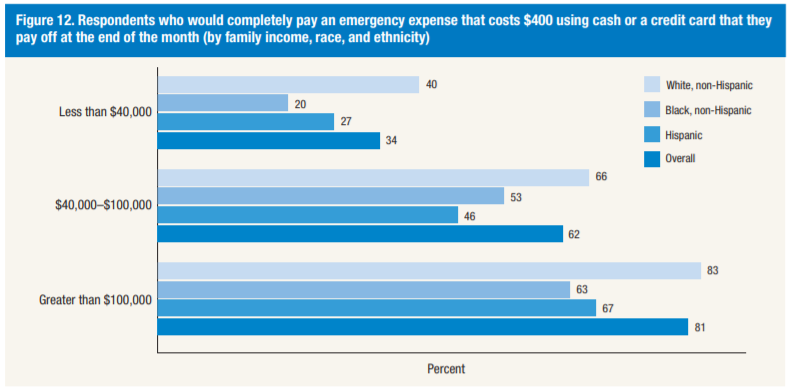

Now that we’ve settled the basics of what it might cost to evacuate a small family for only 5 days, is that something the average American family can afford to do? The answer is a resounding “no.” In 2016, the Federal Reserve asked 5,000 individuals if they could afford to pay $400 for an emergency expense and less than half of them could. The survey results found (unsurprisingly) that 81% of families making at least $100,000 annually could, but only 34% of those earning $40,000 or less were able to afford the expense.

Ability of survey respondents to pay for a $400 emergency by race and income level via the United States Federal Reserve

There were strong racial disparities as well; across all income groups, white respondents were more likely to be able to afford the emergency expense than their economic peers. In the lowest income group (making less than $40,000 per year), the disparity was the most apparent.

Although this is horrific, it’s not unexpected. Racial disparities shape much of American life and who can leave in a natural disaster is no different. When Hurricane Katrina flooded New Orleans in 2005, it was poor African Americans in the 9th Ward who represented the greatest share of the death toll. Until America looks long and hard at the economic and racial disparities in our society (and the intersections between them), we can’t really say we’re preparing for the next disaster.

Are there other barriers to leaving?

Absolutely. Let’s envision a few scenarios in which complications to our Hypothetical Family’s evacuation make leaving even more challenging:

1. Medical complications

The child in our Hypothetical Family is medically fragile and needs regular treatments at a hospital to stay healthy. When their family evacuates, how will they continue to access the care their child needs. Will those hospitals have sufficient bed space to treat their child after receiving the patients who were evacuated from the hospitals where they were being treated? If the hospital where they receive that care is out-of-network, can they afford to potentially pay completely out of pocket?

2. Job security

If one (or both) of the parents in our Hypothetical Family works in the service industry (or for an employer who lacks a public health mindset), Hypothetical Family may be risking unemployment by evacuating the disaster area.

If they are not salaried and exempt, they are not entitled to pay for days when their worksite is closed due to a disaster. If their worksite is open and they do not come in wit shift, they can legally be fired for failing to come to attend work.

3. Supply shortages

When people panic, they hoard. They hoard food, they hoard water, they hoard batteries and candles. When the fear that drives hoarding combines with the very real and practical necessity of filling thousands of cars with gas so people can flee a disaster, the result is miles and miles of fueling stations with no fuel in them.

If our Hypothetical Family hasn’t filled the car they’re planning to drive well in advance, they may not have enough fuel to get beyond the evacuation zone.

4. Road closures and congestion

If our friends manage to pull together the funds and supplies they need, have a road-safe vehicle, and can get the time off work, they are likely to encounter substantial congestion if they’re fleeing a heavily populated area. This can leave them vulnerable to being trapped in their car when flooding takes place or the fire spreads too close to the road.

What can we do?

1. Have a plan before disasters strike.

The Deparrment of Homeland Security has an interactive tool here to help your family prepare for an emergency. Having a plan for where to meet, how to contact each other, and how you’ll get to each other can go a long way. Where I live, disasters come on suddenly, so knowing well in advance what to do is key.

2. Build emergency kits for your household members.

There’s a cost barrier to this one, but even simple kits can help save lives. Some key items which form the backbone of a good kit can come quite cheaply and have a long shelf life:

Dried and nutrient dense foods (e.g., dehydrated fruit, peanut butter);

Flashlights, batteries, and candles;

Basic first aid supplies (e.g., bandages, antiseptic ointment, gauze);

A whistle (to call for help);

A radio which operates on batteries or a handcrank

And fresh water (one gallon per person per day).

In addition to a long shelf life, the dried fruits and batteries can be cycled out periodically for use in your normal day-to-day household needs. FEMA has a resource here for building an regency kit.

If you have pets, include them in your kit too. Extra (dry) food and water; carriers to get them safely into your vehicle; and “mugshots” of them to help identify them should you be separated can help keep your pets safe. The 2006 PETS Act does not require hotels to accept pets, but some may temporarily change their policies to accommodate people evacuating their homes.

3. Help each other.

If you can, check on your neighbours before evacuating. Do they have supplies? Are they able to leave? Can you help each other? Communities are safer and healthier when we care for each other.

4. Listen to and follow Public Health advice whenever possible.

Public health agencies will be broadcasting messages through out the disaster response and recovery periods. As much as you can, try to listen in (we’ll be using the radio!) and follow the advice given. If you need help, contact your local health authorities. (Have their number in your kit!)