We Carry Them With Us: How the Health of our Great-Grandparents Shapes Our Own

Last week was both Columbus Day and Indigenous People’s Day in the United States. Thanksgiving is right around the corner. These days remind me of the stories I heard in school as a child about the “discovery” of America and the “first people” to come here. As an immigrant family, the stories of these holidays weren’t a part of our home life, but they certainly appeared at school each autumn. I remember being told to memorise a poem about Columbus in first grade and the narrative of the first thanksgiving appearing in each US history course I took.

While having time off from school and work is nice (I certainly enjoy that part of civil service), these days are also wonderful opportunities to talk about the health disparities we see between Native American/Alaska Native (AIAN) and other groups in the US. Native writers have spoken and written and researched this far better than I will here, but it’s important for all public health practitioners to discuss the ways that the health of the people who grew us and raised us shapes our own health.

Epigenetics is the study of the way our genes express themselves, which often means examining how environmental factors shape those expressions. Every single person’s health is shaped by the people who came before them. I am, you are, even your cat is. We see the effects of epigenetics in every population, though for this I’ll use my own family’s history and then talk about how epigenetics and Historical Trauma continue to harm AIAN populations in the United States.

These topics are heavy, but talking about them means that we can start to plan ways to correct them. We are more than the products of our genes and our history. My goal isn’t to hurt anyone or to make you feel guilty about harm that your ancestors may have inflicted on others. You are not responsible for their mistakes, but you are responsible for the choices you make now to either uphold or combat systems of inequality.

Northern Ireland

My beautiful great-grandmother Rosina

My family is from Belfast, Northern Ireland, a place that has been poor and plagued by war basically since those things were invented. My great-grandmother Rosina was born in 1912 and missed the Great Famine, but her childhood was still shaped by the civil unrest during the Struggle for Irish Independence. She was certainly undernourished, which made her less healthy than she ought to have been when she married my great-grandfather and started birthing her 12 children.

When my granny was just a tiny little foetus, she carried the egg that would grow into my mother. Unfortunately, it was also WWII and things weren’t very nice in Belfast, an already poor city, and we lived in an especially poor area (New Lodge in North Belfast). My mother’s egg developed in an inhospitable environment just as my granny’s did. There wasn’t enough food, the air was dirty, and Granny left school when she was 10 before going to work in a cigarette factory. My Granny is a tiny woman, but she might not have been if she’d had enough to eat as a child. It’s possible that she could have been as tall as I am, but environmental factors shaped how her genes expressed themselves.

My own mother was conceived during The Troubles, the time that most people picture when someone says “Northern Ireland.” The 1961 Census records that 19.3% of homes in the North had no piped water and 22% did not have a toilet that flushed. I’ve worked in places without consistent access to toilets and I can tell you as a public health practitioner, it makes a healthy life much harder to achieve. It was a very stressful time and place to be and, thankfully, my family immigrated, thus avoiding the worst of it. They went back to Belfast in the summer of 1969, just in time to be horrified at a series of massive riots that displaced almost 2,000 Catholic families. My own mother grew up away from her family, which was safer for her and her younger siblings, but the egg that grew into me formed while my grandmother fretted for her family and adapted to a new country.

My mother used illicit drugs before she had me and almost certainly while she was pregnant (she insists she didn’t, everyone around her says she did). She had a traumatic childhood and parents who weren’t able to care for their living children after their eldest son died, which made my mother more susceptible to substance use disorders. She continued to use drugs at least until the last time I saw her 10 years ago.

I didn’t live through WWII or The Troubles and I don’t have any substance use disorders, but I carry those legacies in me. I’m more likely to have heart disease, respiratory disorders, and mental health issues because of not just the genes they gave me, but their experiences that shaped the ways in which those genes expressed themselves. I carry both the genetic and epigenetic legacies of the women who passed down their genes and their experiences to me. I am in real and tangible ways the product of their experiences.

North America

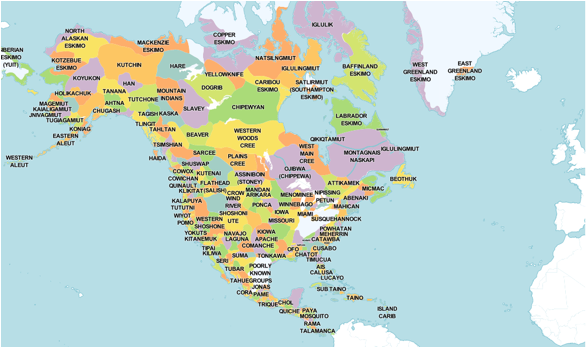

My family has experienced real and intense trauma, but it is small potatoes to the widespread state violence that native populations in North America have suffered. North America wasn’t empty when Europeans came to Jamestown, Plymouth, Raleigh, or anywhere else. The Americas were full of people who had languages and politics and art and lives as rich as European ones. They didn’t invite a wave of immigration that brought them measles, smallpox, and influenza–diseases they were unprepared to fight because their immune systems had never encountered them. Native populations neither peacefully gave up their land nor did they “lose” their territory because they were less technologically capable of fighting for it. They were wiped out by pandemics beyond anything we have seen since then.

The new governments that sprang up in Canada and the United States made “agreements” with the nations already here to take their land, but those were very seldom honoured. Communities were forced out of their homes (sometimes they had to walk across the country). Children were taken from their families and taken to residential schools so that the government could, “kill the indian, and save the man.” The children were then forbidden from practicing their religions, taking traditional medicines, and even from speaking their own languages. These residential schools weren’t just a relic of the past, the last residential school in Canada closed in 1996 and the children who were held captive there are just beginning their adulthood. What legacy will the trauma they experienced at the hands of their government leave on their children?

There are a variety of terrible effects from this legacy of trauma–AIAN populations have higher rates of chronic and infectious diseases, and native women are dramatically more likely to be assaulted than their white peers. Reservations are among the most impoverished areas of North America and some Tribal Nations are without drinkable water. When the Water Protectors in North Dakota asked for existing treaty rights to be respected and the Dakota Access Pipeline Diverted, they were repeatedly assaulted by agents of the United States, state, and local governments. (Content notice: the images and descriptions of violence in that article may be upsetting.) The health effects of this intergenerational trauma is well documented and we have a social responsibility to understand not only that heart disease is more common in native peoples, but also why it is more common.

I would like to note here that there is also tremendous resilience in native communities. Despite experiencing centuries of genocide and colonization, communities still come together for beautiful gatherings like the Lummi Island Canoe Journey and to build fantastic gathering spaces like the wǝɫǝbʔaltxʷ – Intellectual House at the University of Washington. Tribal Nations produce incredible scholars like Dr. Bonnie Duran, DrPH, MPH and Dr. Myra Parker, JD, PhD, MPH. We are very much the products of the people who have come before us, but that means that protective factors from them can also come to us.

What to Do?

We know that the social and physical environments in which we live form a substantial part of our health, but how we as a society can get there is a more challenging puzzle to solve. I feel like it’s the rallying cry of my generation, but among the best ways to enact change is to demand it from your elected officials. You can find a listing of the people who represent you in Congress (if you’re in the US) here. There are equally convenient links if you’re in the UK, Ireland, or Canada.

You can also enact change by with where you spend your dollars/pounds/euros. Support organizations that do good work that supports public health, especially those that support the health of communities of colour. You can even directly support businesses owned by communities you want to support. There are convenient lists for native and black owned businesses.

Think critically about the ways that you uphold health inequities through direct action or through inaction. Do you participate in harmful stereotyping of native communities when you dress up for Halloween? Do you pass down a false narrative of how America was “founded” when you talk about Columbus Day or Thanksgiving? Do you unconsciously pass over native women in your work–particularly for positions of authority? Are you acknowledging the people on whose land you live?

You can be an agent of change for good in your community and we can overcome our epigenetic legacies. In two generations, my family went from children working in cigarette factories to children having scientific careers and economic stability. All children who come from a legacy of trauma deserve the same opportunities that I have had and it’s only by consciously working to end health inequities that we can achieve that.

My Granny holding me a few weeks after I was born. I am the product of the trauma she carried down and the sacrifices she made for a better life.